[THEATRE and Physical Theatre/Theatre ~ AUSTRALIAN PREMIERE ~ UK]

by Adrian Miller.

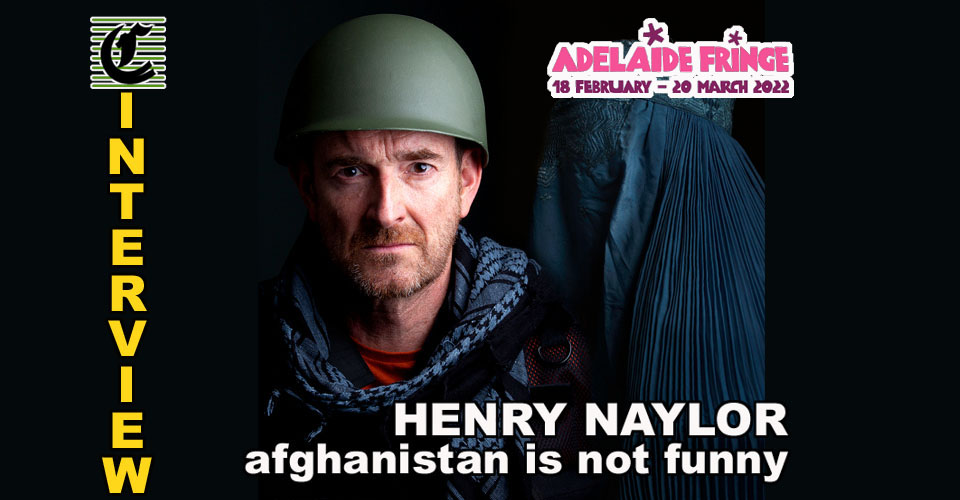

Henry Naylor has become a regular feature of the Holden Street Theatres’ Fringe program, but always as a playwright bringing incisive plays to be performed by other actors. This year he is stepping into the spotlight himself. The Clothesline contacts Henry to find out more about this decision, and ask why he chose now to write about Afghanistan:

AFGHANISTAN IS NOT FUNNY is very topical given the recent downfall of Kabul. Does this mean this play has been written since you were last at the Fringe, or is it a reflection of your time there that you have been working on over a longer period?

“I started writing this play because of the rise of the Taliban,” Henry says. “I’ve got friends out in Afghanistan. And I’m concerned that under this new regime, their lives may be in danger. Furthermore, with the Taliban returning to the power, Afghanistan may disappear from the public consciousness.

“In the past Western journalists have been executed by Taliban forces. So, there may be a return to kind of Dark Ages, where coverage of Afghanistan is limited. News editors will be reluctant to send their staff to the country.

“In the absence of news coverage,” he says, “I feel that the arts may have to step up: the only way to try to keep Afghanistan in the public consciousness, is through art. That’s why I decided to write this play.”

The previous shows you have brought to the Adelaide Fringe have always contained bravura performances from compelling actors. This year you have taken on the acting yourself. Do you feel under any pressure from this?

“Yes, I have been very lucky with my casts in previous years at the Adelaide Fringe. Filippa Bragança, Felicity Houlbrooke, Avital Lvova and Graeme O’Mara – among others – are supreme performers. But this year’s show is such a personal story, it couldn’t be performed by anybody else but me.

“Some of the events within AFGHANISTAN IS NOT FUNNY are so unbelievable,” Henry says, “that if they were scripted as a play, people would dismiss them as too far-fetched. It’s only by appearing here on stage, relaying my personal stories, that I can give them their truth.

“I guess as a performer, I don’t feel any pressure, because I have been a comedian for many years. Sure: I haven’t been on stage doing solo work for nearly 15 years, that is true. But it’s like riding a bike: you never truly forget what you’ve learned.

“Also, many of the stories within the show are stories that I’ve told a million times in the pub. They’re quite honed pieces of material so I probably don’t feel the nerves that I would if I was playing a fictional character.”

Despite the serious topics covered, your plays they always contain jokes that prevent the heaviness from becoming unrelenting. Can this in part be explained by your experience as a comedy writer and that you find drama more compelling with a bit of humour included?

“I think it’s a very human thing to laugh at a time of dread. It’s our way of coping,” Henry says. “One of the funniest people I know, and I talk about in the play, is a war correspondent. He has seen some truly dreadful things. And yet, down the pub, there is no one more amusing. He is funnier than any comedian I know.

“One of the things I aim to do in my work is to try and make difficult or unpleasant material palatable; to help an audience look at subject matter which they would otherwise find too grim. If I didn’t have the jokes, the funnies and the amusing anecdotes, it would end up being an unrelenting gloom fest. We are, first and foremost, entertainers. I don’t want to berate my audiences like a priggish school ma’am. I want to take my audiences on an emotional journey to make them laugh, to make them cry, and to tell them some things they may not have known before.”

It seems odd that Afghanistan would ever have been chosen as a place for a comedy writer to visit. Did you have a more serious purpose when you first went there?

“It’s not really that surprising, when you consider what I was doing at the time. It was 2001 to 2003. It was the time of the war with Afghanistan – and its immediate aftermath. At that time, I was writing for a topical Radio show. Afghanistan was consistently the main story in the news. I was writing jokes about the country – and researching it – every day. Inevitably, I was curious. And perhaps, obsessed. I wanted to write about it in more depth than comedy skits on the radio. I wanted to write a play. In fact, it was that war which launched me into my new career as a playwright, rather than a comedian.”

You went to Afghanistan with photographer Sam Maynard. Is his work featured in this play?

“Yes, Sam’s work is all over the show,” Henry says. “Part of the show is a slideshow, showcasing his photos from Afghanistan. There are over 70 of his pictures – and believe me, they are brilliant. Which is hardly surprising. Sam is one of the best photographers in the British Isles. He won Scottish Photographer of the Year two years running. The show is a visual feast because of them… If the audience get bored with looking at my ugly mug, they can always look at Sam’s beautiful photos!”

In the play you tell us how your life was in danger many times. Has that changed the way you look at life and the work you do?

“It’s definitely affected the way I looked at writing topical news,” he says. “By going to a war zone, I felt I was participating in global events, rather than observing them. Perhaps it made me more responsible with my comedy. Perhaps it made me understand the devastating effects of politicians’ policies upon real people, and gave me a greater sense of empathy. It certainly made my satire more biting.

“Undoubtedly, it’s why I started writing plays. Plays give me the space to write about the impact of world events on ordinary people. To show how devastating they can be. You rarely get the chance to do that in a comedy sketch show.”

You have been a regular visitor to the Adelaide Fringe. You obviously feel safe here?

“I love it in Adelaide. I adore the Fringe Festival. By coming over many years I’ve got a lot of friends here now. And also you’ve got unbeatable weather. At this moment there are storms which are virtually blowing Britain into the North Sea. By being here, I’ve dodged them. Instead, I’m zoom-calling friends and family at home and irritating them with my suntan.”

Does your play have anything to say about Australia’s involvement in the Afghanistan war?

“Well, I think the issues in the play are applicable to everyone in the West. We’ve all, internationally, neglected Afghanistan,” Henry says. “The last 20 years have been a tale of mismanagement – by all countries. I feel desperately sorry for those people who enjoyed the benefits of a liberal society, and now will have to live under an oppressive regime. It’s particularly troubling for the women out there. And some of my friends too. One of my good friends out there works for the UN. He’s now in hiding.”

What do you want people to take away from your play with regard to having empathy for the Afghani people and feeling a need to help in some way?

“If in some tiny way, I can help keep Afghanistan in the public consciousness, that’s all I can really hope for. Of course, I’d love to be able to inspire ‘those who can make a tangible difference’ into action. But hey, you have to be realistic.”

Is there any hope for a brighter future for Afghanistan contained in your script, or have things deteriorated beyond any hope?

“Afghanistan is constantly changing,” Henry says. “Every 10 to 20 years a different regime is in power. Back in the ‘70s there were women in Afghanistan who were wearing miniskirts… then came the Russians… then came a regime which was so oppressive that women were beaten for exposing their ankles. And then came a fragile democracy.

“I know people are depressed about the Taliban being in power, but I’m sure the situation will change again. Maybe not even for the better. There are more extreme forces even than the Taliban in the region. But not even they will last.”

Is there anything else you would like to tell us?

“I would just like to encourage anybody to see shows at the Fringe this year. Not just me. Anybody! Try and see more shows than usual! It’s been a tough couple of years, particularly for artists. In the UK, the Arts got very little support from the government during the lockdowns. I know it was similar in Australia too.

“The artistic community has been hit harder than most,” Henry says. “And yet we mustn’t forget that it was the arts which kept us all going during the lockdowns. It was the series on Netflix, it was the movies, it was the TV we watched, it was the YouTube videos, it was the podcasts… Please support artists so we can get you through the next pandemic!”

AFGHANISTAN IS NOT FUNNY by Henry Naylor continues at The Studio at Holden Street Theatres, at various times, until Sun 13 Mar.

Book at FringeTIX on 1300 621 255 or adelaidefringe.com.au. Click HERE to purchase your tickets.

#ClotheslineMag

#ADLfringe

#HST