by Bobby Goudie.

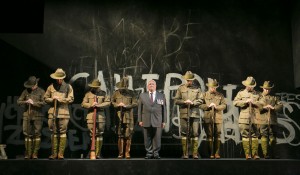

Black Diggers presents the untold stories of Aboriginal soldiers fighting for Australia during World War 1. Written by Tom Wright and directed by Wesley Enoch, Black Diggers has received superb reviews at the Brisbane and Sydney Festivals. The Queensland Theatre Company is bringing the all-male, all-Indigenous cast to reclaim a forgotten chapter of Australia’s war history to the Adelaide Festival. This year marks the centenary year for WWI and Black Diggers looks to be a poignant narrative in the remembrance of those who left to fight and never returned.

Wesley Enoch is of Murri descent and a proud Noonuccal Nuugi man. During his time as Artistic Director of the Queensland Theatre Company he has presented productions that include The Sapphires, The 7 Stages Of Grieving, Stolen and Riverland.

The Clothesline speaks with Wesley and asks how Black Diggers came to be.

“The starting point was a dinner I had with Lieven Bertels who is the artistic director of the Sydney Festival,” he begins. “He was telling me of a war cemetery close to the Belgium village he lived in, and a grave site there of a digger called Rufus Rigney; an Aboriginal man who comes from Raukkan in South Australia (on the banks of Lake Alexandrina near the mouth of the Murray River).

“It is fantastic story,” Wesley enthusiastically continues. “When Rigney was 16 he signed up to become part of AIF [Australian Imperial Force]. He went over and fought but, sadly, died in Flanders Fields during the battle. When hearing the story, I thought about this deep cultural sense of what does it mean to die in a different country and what ceremonies are done. We talked about this and I ended up going over there to visit Rigney’s grave. My guide went to look where the grave was, but I picked it instantly. Taped on the side of the gravestone was an Aboriginal flag, as well as photographs and certificates. It’s basically a whole shrine.

“Rigney’s family from Raukkan regularly go over with school kids. They perform a connection ceremony to his homeland and Raukkan and the gravesite in Belgium. They do this incredible thing where they take dirt from his homeland and put it on his grave and then take dirt from his grave and bring it back to Raukkan. There is a whole ceremony of singing, playing didgeridoo and dancing around his grave as a connection and commemoration of his service. It’s extraordinary.

“There in the church in Raukkan, I would say, is the first Indigenous war memorial in the country,” he adds, “with a stain-glass window memorial. I’m paraphrasing, but it says something like, ‘For those who fought and gave their lives for freedom and liberty’. Not king and country, but freedom and liberty. There was a real sense of Indigenous presence. I was so fascinated by this extraordinary story.”

There was a strong relationship formed with the Australian War Memorial to research for Black Diggers. Wesley remarks that this research has changed formal records in Australia.

“When we started, the Australian War Memorial said they had between 400 and 500 names of Aboriginal soldiers who fought in WWI. Then when began rehearsal they informed us they now had 800 names. By the time we opened the show, the list had grown to over 1300.”

Wesley tell us that records were taken at the time of the White Australia Policy and therefore there were significant problems in the record keeping of Aboriginal people involved in WWI.

“The charter of the AIF said that you needed to be substantially European or of substantial European origin to join the AIF. Lots of Aboriginal men were just rejected. Eventually following two referendums about conscription and needing more men, more Aboriginal men were let in. The medical officers just had to turn a blind eye to the fact that they were Aboriginal.”

Black Diggers – Image courtesy of Jamie Williams

So how did the data and stories you gathered become a theatrical experience?

“Following the research process we brought writer Tom Wright on board,” Wesley says. “People would write of Aboriginal servicemen from their non-Indigenous perspective, but we wanted to tell stories from a different perspective. We went to the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission where they explained four definitions of truth:

The first is the truth that you believe is absolutely the truth.

The second is the truth that is reported on in newspapers and by government.

The third is the forensic truth that science can prove.

The forth truth category is the community truth or the healing truth; truths that are discussed for the purposes of bringing people together.

“All four definitions were useful for us; each fitted into different aspects of the stories,” he continues. “So when we were making this theatre piece, we weren’t about telling a factual biographical story, but more of an indication of what the experiences where. Everything in the show is based on a document, formal history or an oral story that has been passed down that was given to us.

“When I went to Raukkan and met the family of Rufus Rigney, the stories they have are oral stories passed down,” he remarks as an example. “Nearly 100 years of passing down these stories about who this man was. They have this amazing story that he was six-foot-tall and built of steel. He was a great hero, but of course the records don’t have this larger narrative. We wanted to include these oral stories.”

Is there anything that really surprised you in the Black Diggers journey?

“When we started telling people about the show, it was surprising to see how interested people were,” Wesley says, enthusiastically. “They had really never thought too much about Aboriginal people in WWI. They hadn’t really considered what Aboriginal people’s role in WWI was. People were surprised that Aboriginal people would even want to fight for a country that doesn’t recognise their citizenship.”

What is it like for the families seeing these stories come to life in front of them?

“There is an outpouring of emotion. These are very individual stories and ones they are personally proud of. Some of the relatives say they feel their stories have been told and are proud to have them out there for others to see and hear. One of the relatives told us how important the show was and how 4 or 5 generations of his family has committed to a life in the military. It was fantastic to hear what it has meant for them.”

Tell us about the cast.

“We have a broad age-range of performers in the show,” he explains. “The youngest is 21 and the oldest is 76 and a Vietnam veteran – Uncle George Bostock. One of the final images of the play is him wearing his own medals on stage. Each performer plays a huge amount of characters throughout the show, from Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people, and even women. There is a very fluid sense of character, and having an all-male cast gave me a great opportunity to see how mateship, camaraderie and competitiveness happen with men. Mateship formed among the cast and you got a sense of how it must have been like during the war.”

With Black Diggers set to perform in Perth, Melbourne, Bendigo, Newcastle and Canberra this year, Wesley expresses his excitement at performing during the Adelaide Festival and tells us that there are hopes it will then tour overseas to share this unique Australian experience.

“We are so glad Adelaide Festival has picked this piece up,” he says. “I think David Sefton has been great for the Festival in the way that he sees Australian culture and in the way Australian and international cultures can sit side-by-side; they don’t have to be separate.”

Black Diggers performs at Her Majesty’s Theatre at various times from Tue Mar 10 until Sat Mar 14.

Book at BASS on 131 241 or bass.net.au. Click HERE to book your tickets.

Cover image courtesy of Branco Gaica