[PERFORMANCE BLOG ~ UK]

by Roman Ackley

I write this while getting ready to do a striptease at After Dark Cabaret in Kings Cross. This morning I’ve pruned, primped and shaved (various areas), as well as umm-ing and ah-ing over my props (I never change them for this act, but the ritual indecision seems to be important somehow). I’d like to write about performing without much clothing on, and how I understand the difference between ‘nude’ and ‘naked’.

Nude.

Life modelling is the act of posing, often without clothes, for people to draw you. I was raised in a very formal tradition of life drawing – you don’t strip, you disrobe, and you aren’t naked, you’re nude. This isn’t a real differentiation but people treat you very differently. Nude is The Vitruvian Man, The Thinker, the collective works of Michaelangelo Buonarroti.

My first life drawing class was aged 17, with a pregnant model who was able to sit in a pose for extended periods. I guess there’s always something to think about when you’re pregnant, and you’re more or less always in a sort of ‘conversation’. She always had this amazing look on her face like she knew something everyone else didn’t. I remember being very concerned about objectification (we were doing feminist theory in social studies) and taking a great deal of time trying to capture her face and expression. Anyone with art training will tell you I had got that quite upside-down; portrait and life drawing are very different exercises.

There’s little point in someone posing nude if you’re going to spend half the time fussing about drawing their nose straight – so I was effectively wasting her time, an act of terrible disrespect in life drawing circles. Assuming that drawing someone’s face avoids objectifying them or that the personality can’t be expressed in the body was also a tad naive. We put huge judgemental weight on both the face and the body. Gradually I got used to the absurdity of about 30 clothed people staring at one naked person and pointedly not talking about it. Rapidly you start to develop a draftsman’s eye, one that sees, without judgement or favour, only light and shade, mass and space.

In contrast, a friend had an awkward first experience – the bloke walked in and unceremoniously bent over. Not a beginner’s pose – or a particularly aesthetic one; zero time to adjust to artistic analysis of the human form there. He was not nude, but naked. She compared the experience to being flashed and never drew from life again- she has since become an excellent architectural drawer.

I had been drawing for about a decade before someone asked me why I hadn’t tried it myself; it occurred to me it was because I would be embarrassed. In effect, I had been expecting other people to do something I would be too embarrassed to do. I didn’t like what that said about me and promptly auditioned for a registry. Mirror Does Not Love You Like This is a beautiful documentary that sums up the experience. When you know how an artist is looking at you – as lines, shapes forms, that they need to represent on a page without judgement, there’s a lot of acceptance there.

People have a lot of hang-ups – I once had someone in a class say that she’d consider modelling once she had finished her career in Law. This is probably sensible as the legal system in the UK puts a huge emphasis on reputation and respectability. Rationally, I can argue that the study of anatomy has been central to European art for at least 3000 years – but I have little faith that this would hold up against the inherent squeamishness of the British when faced with the human body.

So for the purposes of this article, I feel like I’m a nude when I’m unclothed, and viewed dispassionately in a studio environment. You’re effectively clothed by the trust that you have in the artist that they are looking at you a certain way. The nude is always in danger of becoming ‘naked’ – an embarrassing surprise, like that dream where you have an exam you haven’t studied for and your trousers fall down. One of the most controversial nudes of the 19th Century was Manet’s Olympia who, shock horror, made eye contact with the viewer. For that audience, this broke the rules and made her ‘naked’ (scandalous!). When I’m tutoring and the model won’t hold still because he’s chatting, he magically transforms from being a nude model to a naked man.

Naked.

Naked is walking in on your flatmate in the shower, your lover waking up next to you in the morning, a friend sharing a rare confession. The oddest thing for me about modelling and burlesque is how, even though you keep significantly more clothing on in burlesque (bar ‘costume malfunction’), I do feel considerably more naked. Generally, in burlesque you don’t see more than you would on the beach, although you do get full frontal in some venues and shows (if they can do it in Equus why not in a comedy?).

People often describe that feeling of nakedness in other performance disciplines. When I sing I can be in a three-piece suit and feel much more naked than if I were silent nude. If someone read your diary, you would feel naked – not nude. For a lot of performers that feeling of exposing yourself on a metaphorical or physical level is what you are there for – it’s part of sharing yourself with an audience to an extent you feel comfortable, and them responding to that vulnerability with love.

Burlesque derives from one of the many Italian words for comedy. Like many art genres, its definition is broad, varied, and changeable, to the extent that what counts as within the discipline is more or less what practitioners and audiences reach a consensus on at any one time. We’d spend weeks arguing over a shared definition but people often know it when they see it (see Grayson Perry’s excellent Reith Lecture Beating The Bounds for a strong exploration of this pragmatic approach to defining art). It often fits within the similarly fuzzy concept of ‘Cabaret’ – performance in an intimate space, with no emotional wall between the artist and the audience. And with that exposure of emotion, you are naked, not nude.

That said, if you see ‘burlesque’ on the bill you might reasonably expect someone to take at least a glove off. In the spirit of defining a term by its use, we could describe it as entertainment including but not limited to striptease. But then I’ve also seen people leave the stage with more clothes than they came on with, or have costumes that transform or re-shape – from a showgirl to a peacock or similar. Some people define it as having some form of story, joke or skill.

[There is a lot of clown-type performance in there but we keep that on the down-low since Stephen King’s It ruined clown’s brand again (‘It’ has been about as disastrous for clowns as ‘Jaws’ was for sharks).]

I dispute the idea that skill separates burlesque and stripping: pole dancing, for instance, is literally acrobatics, incredibly hard, and physically demanding. I threw my back out after three sessions. I’m also not a fan of any definition that implicitly devalues another form of performance – this is about differentiating, not devaluing other people’s hard work. For others, part of the definition is that burlesquers create their own acts so it is an independent act of self-expression using their own body. A terminal fence-sitter and wilfully unhelpful, I would describe burlesque as any performance a burlesque artist defines to be burlesque.

I became involved in ‘boylesque’ in more or less the same way as modelling, having attended cabaret shows as a civilian for about a decade. Many years later a producer friend caught me on an unusually gin-filled evening and recruited me in the war of art. I took her course and three months later was grinding the stage in a jackal mask, in a performance that experts described as ‘worrying’. My first few acts I felt the need to wear a mask to establish a character, even in underwear, despite having been fully unclothed in the studio. Why? I had a number of feelings about it. I was expressing myself differently, moving, making eye contact and interacting. The love was different – less analytical, more verbal, something more about the heart than the eyes and the hand. The audience certainly aren’t seeing you dispassionately as a series of lines and angles. And they are supportive, but in a very different way than someone shyly showing you their pastel drawing of the nape of your neck.

I don’t think many performers make this conscious differentiation between naked and nude. Neither one is better than the other. I do know that people treat me differently in the studio and on the stage, and that misunderstandings arise when people treat you one way or the other. Whooping and growling in the studio doesn’t go down well. Silently and objectively examining a burlesque artist with your eyes and making observations on paper will usually make for a bad night all round. The commonality is that both have a culture of appreciation that avoids treating people’s bodies with the casual judgement that our culture encourages.

In either case I suppose we’re people, sharing our bodies and minds with a room of strangers, and hoping to be seen kindly.

Roman Ackley is a model, burlesquer, sketcher, fire breather, sword-swallower, glass-walker, actor, writer etc. etc… Get your regular dose of London Cabaret Dispatch here, or play along at home by following him at facebook.com/RomanAckley.

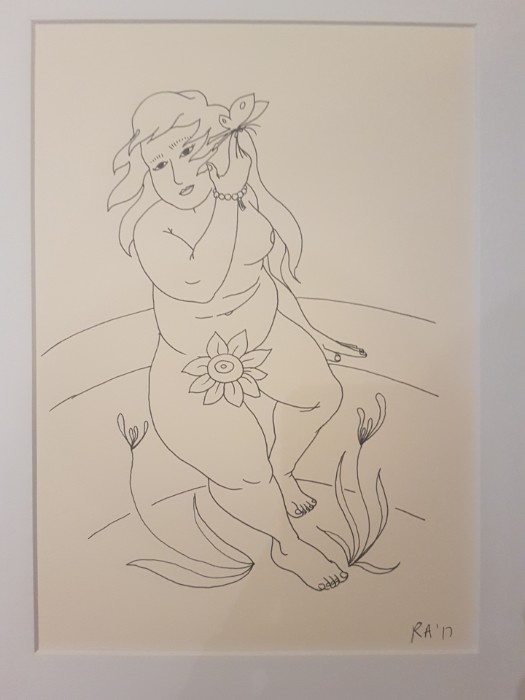

Hand-drawn image courtesy of Roman Ackley

Roman Ackley image courtesy of Feather Photography